- Home

- Diana Mosley

The Duchess of Windsor

The Duchess of Windsor Read online

THE DUCHESS OF WINDSOR

Diana Mosley

GIBSON SQUARE BOOKS

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 A Young Lady from Baltimore

2 Navy Wife

3 The Little Prince

4 Prince of Wales

5 Divorce and Remarriage

6 Ich Dien

7 Mrs Simpson meets the Prince

8 The Prince in Love

9 Loved by a King

10 Storm Clouds

11 Abdication

12 King into Duke

13 Marriage

14 The First Two Years

15 War

16 The Bahamas

17 The Windsors in France

18 The Brilliant Duchess

19 Old Age

20 Summing Up

Notes

Index

Copyright

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the following, who have given me invaluable help in writing this book: Jane, Lady Abdy; Mrs Herbert Agar; the late Sir Cecil Beaton; Lady (Rex) Benson; Ann-Mari Princess von Bismarck; Mâitre Suzanne Blum; Comtesse René de Chambrun; Father Jean-Maria Charles-Roux; The Lord Colyton; Grace, Countess of Dudley; Sir Dudley Forwood Bart; Mme Jean Gaudin; Dr Henry Gillespie; Marquis de Givenchy; Mr John Grigg; Mr Horst; Mr James Hudson FRCS; Mrs James Hudson; Mr Geoffrey Keating; Mr Walter Lees; The Lady Elizabeth Longman; Prince Jean-Louis de Lucinge; Miss Rose Mary Macindoe; Mrs McLaughlin; Mme Igor Markevitch; Mrs Metz; M. Hervé Mille; Major-General the Viscount Monckton of Brenchley; The Hon. Rosamond Monckton; Sir Berkeley Ormerod; M. Gaston Palewski; Miss Fiona Da Ryn; M. Maurice Schumann; The Countess of Sefton; Miss Monica Sheriffe; Professor Robert Skidelsky; Mr John Utter; Mrs Diana Vreeland; Miss Margaret Willes. My special thanks to Lady Lloyd, who allowed me to quote from an unpublished memoir written shortly before his death by her uncle, Captain the Hon. Bruce Ogilvy, who was equerry to the Prince of Wales for nine years.

I should also like to thank the following for permission to publish extracts from copyright material in their possession Allen & Unwin Ltd for Queen Mary, 1867-1953 by James Pope-Hennessy (1959); W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd for The Woman he Loved by Ralph Martin (1974); Jonathan Cape Ltd for The Slump by John Stevenson and Chris Cook (1977); Cassell & Co. Ltd for A King’s Story: The Memoirs of H.R.H. the Duke of Windsor (1951); Collins & Co. Ltd for Diaries and Letters 1930-9 by Harold Nicolson (1966); Constable & Co. Ltd for Winston Churchill: The Struggle for Survival by Lord Moran (1966); Evans Brothers Ltd for Your Dear Letter: Private Correspondence of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, 1865-71 edited by Roger Fulford (1971); Eyre & Spottiswoode Ltd for Editorial; The Memoirs of Colin R. Coote (1965); Hamish Hamilton Ltd for Victor Cazalet by Robert Rhodes James (1976); Hart-Davis MacGibbon Ltd for The Light of Common Day by Lady Diana Cooper (1959); Michael Joseph Ltd for The Heart has its Reasons by the Duchess of Windsor (1965); La Pensée Universelle for Mon Dieu et mon Roi by Jean-Maria Charles-Roux; Macmillan Publishers Ltd for Life with Lloyd George by A. J. Sylvester (1975); and the Earl of Airlie for Thatched with Gold by Mabell Airlie (1965). Picture acknowledgements where not part of the author’s private collection may be found in the earlier edition of the work.

Introduction

From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever Gods may be

That no man lives forever,

That dead men rise up never

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to seas.

Swinburn

WHEN THIS BOOK was first published, the Duchess of Windsor was still alive, but she never saw the book. Her heart was beating, therefore she was alive, but she was fed artificially and supposed to be unconscious of her surroundings. She had three nurses, doctors, a solicitor; no visitors were allowed. There was a notice in the hall of her house, signed by her doctors, forbidding them. In any case, she would not have known her visitor, or registered that somebody had come to see her. Relations would have been allowed to see her, but she had none. She had in-laws in England who also would have been allowed to see her, but there again they would have seen a body lying in bed ‘beautifully looked after’ as an English doctor put it.

Nobody knows whether people in this distressing condition can think at all, whether they dream, whether they have nightmares. I heard recently of a case involving a male patient. His daughter said to the doctor how very sad his expression was. The doctor dismissed the idea that he might be sad, saying he was completely unconscious and felt nothing, but the daughter insisted, and the man was finally given an injection. The expression on his face changed at once.

The last time I saw the Duchess she looked absolutely miserable and tragic. Whether anything was done to help her I don’t know. In such cases the great need is for family who realise there might be ways of helping. After my last visit, she lived for ten more years. Even ten days would have been too much. She was kept ‘alive’ until she was ninety. It is a terrible, haunting thought that she may not have been as completely unconscious as the doctors supposed.

Her solicitor, Maître Blum, was a very forceful character and she idolised the Duchess. If on the medical side it is impossible not to feel that, in her isolated condition—without a single relation who might intervene to help her—she had almost incredible misfortune, on the legal side she was extremely lucky. Me Blum realised she was in charge of a very important archive. She chased away anyone rash enough to try and get hold of it, or to suppress the truths it contained.

She in her turn had good fortune because the young barrister who joined her chambers in pursuit of a career as an international lawyer was Michael Bloch, who as time went on became an excellent writer. Perceiving this Me Blum gave him the Windsor papers to work on and he produced books, of which the best is The Duke of Windsor’s War. Tracing the Duke’s activities day by day from 1939, and until he sailed from Portugal to the Bahamas of which he had been appointed Governor in 1940, the book answers various calumnies of which the Duke has been the victim in England’s yellow press by describing what actually happened.

Quite simply, the Duke wanted to serve his country in England, but it was made plain to him that the Duchess would not be treated as his wife should have been. He therefore reluctantly accepted the offer of a governorship of the Bahamas, staying there until the end of the War. There appears to have been jealousy of his charm and popularity, not bestowed by fate on other members of his family. If he were sent thousands of miles away, the memory of what he had been would gradually fade. It was quite a clever idea, and as time went on he himself was less anxious to go to England—his home was wherever the Duchess might be. Winston Churchill, who as Prime Minister had to give the Duke the order to go to the Bahamas, significantly added the words ‘I did my best.’

When he abdicated, the new King had promised that after an interval he could come back from time to time to Fort Belvedere (in Berkshire), the house he loved so much. But this was a gentleman’s agreement, there was nothing written down, no legal arrangement. The Duke would never have resorted to the courts, because in his opinion such a move would have injured the monarchy. It was the same with the Duchess’s title, lawyers agreed he would have won his case but an action at law was something he declined to contemplate.

It is impossible to exaggerate the loneliness of the Duchess of Windsor’s last eight years of life. She had one friend, her butler Georges Sanègre. He was an exceptional person, not only an excellent butler with a very charming personality but he was truly fond of the Duchess. When she was no

longer allowed to see friends, I went to her house to talk to him. I asked him to promise to telephone me and tell me if, for example, one of the nurses was less than kind. I went quite often to see him, he and his wife Ofélia must have felt as if they were living in a tomb.

After a couple of years he telephoned and asked me to come. I went at once, wondering what I could possibly do if there was bad news, I had no status whatever as a mere friend. However, he wanted me for quite a different reason. He showed me the dining room where he had arranged the table as if for a grand dinner, with all the loveliest china and vermeil, as it was in the old days. Apparently there had been stories in the newspapers that the Duchess’s beautiful things were all disappearing, and I was to be able to say that this was nonsense. In the event I was never asked such a question.

The presence of Georges in the sad house in the Bois de Boulogne was very important. It would have been far worse without him; she might have wondered, in moments of lucidity (if there were any) what had become of all the people who had flocked to her house, and whether she was completely abandoned by everyone.

As years went by, the fact that nobody saw her gave rise to all sorts of theories and stories, usually complete inventions, often putting the blame unfairly on Me Blum. Like the excluded friends, Me Blum obeyed the doctors, and the doctors followed their oath to save life and preserve a patient from death. In view of the horrible consequences of this oath, at the very least the word ‘life’ must be given a new meaning. It cannot continue to mean a very old unconscious body with a beating heart. The visitor to an English hospital, looking at a huddled old body in a bed, said ‘What is her life?’ ‘Eat and excrete’ was the reply.

The Duchess had, of course, many in-law relations, the royal family in England. They had the right to see her, and if necessary make suggestions. It seemed to me that if a conference of doctors, English, French and American, were called something more humane might have resulted, but the initiative had to come from them. Reluctantly, but nobly, an English surgeon agreed to attend such a conference. Doctors hate confrontation, collaboration is their rule. But this was a uniquely terrible case. Courage and humanity for an initiative were not forthcoming. Did she, for example, still have the tragic expression which had so struck me the last time I saw her? And if so had anything been done to alleviate her misery?

The Duchess died in April 1986. She was buried near the Duke at Frogmore after a very beautiful funeral in St George’s Chapel at Windsor.

Diana Mosley

Paris, Summer 2003

Der du, ohne fromm zu sein, selig bist!

Das wollen sie dir nicht zugestehn

Goethe

AT A DINNER party in Paris in the 1960s somebody asked the question: ‘What would you wish for if you could have one wish?’ Variations on the theme of health and wealth as a means to happiness followed, with the accent on wealth. The Duke of Windsor was one of the guests; he remained silent until prodded by the Duchess. ‘Tell us what you would wish for?’ she said.

‘You,’ was the reply.

Nobody who knew them doubted that this answer was simply the truth. She was all the world to him. They had been married for upwards of thirty years, and the drama of their marriage had faded into an historical happening from before the war. The brother who had succeeded him had been a popular King; his niece an even more popular Queen. A cynic might suggest that the Duke of Windsor was obliged to count the world well lost for love, since he had thrown the world away and could therefore never admit to having made a mistake. But the cynic would be quite wrong.

To try and discover something about the woman who inspired such a deep and lasting love, and the man who lavished it upon her, is the purpose of this book.

Diana Mosley

Temple de la Gloire, Orsay, 1980

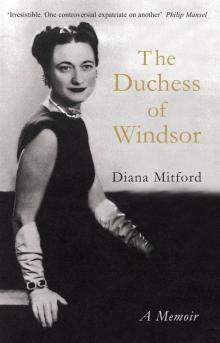

When Cecil Beaton visited Wallis at Cumberland Terrace in 1936 with proofs of her photographs, the King asked for all prints. ‘Won’t that be rather a Wallis Collection, Sir?’ quipped Beaton. This portrait of Wallis was photographed by Beaton in 1934.

CHAPTER ONE

A Young Lady from Baltimore

I was born an American. I will live an American, I shall die an American.

Daniel Webster

BESSIE WALLIS WARFIELD was born on 19 June 1896 in a summer holiday cottage at Blue Ridge Summit in Pennsylvania, but this was purest chance; the birth was a little premature and the parents had gone to Blue Ridge Summit because the baby’s father was in delicate health and wanted to escape the heat of his native Baltimore, where it had been planned that the child should be born in the family house.

The Warfield family came to America in 1662, and Wallis was descended from Governor Edwin Warfield of Maryland. They were long-established and well-regarded in Baltimore. Her mother was a Montague from Virginia; a relation of hers was Governor of Virginia from 1902 to 1906. The Montagues were famous for their good looks and their sharp tongues. In her memoirs the Duchess of Windsor repeats some of her mother’s wisecracks; they do not strike the reader as particularly witty, but they evidently seemed so at the time. ‘Oh, the Montagueity of it!’ exclaimed people in the know when Wallis herself made an amusing remark.

All four grandparents had supported the Confederate cause in the Civil War thirty years before; they were pro-British and anti-Yankee. They were proud of the fact that Wallis’ Warfield grandfather had been arrested ‘by Mr Lincoln’s men.’ He had died before Wallis was born, but her grandmother had a hatred of Yankees that would have startled even Jefferson Davis, and never allowed a Northerner into her house. ‘Never marry a Yankee,’ she used to say.

When Wallis (she dropped the Bessie as a small child, saying it was the name of so many cows) was a few months old her father died at the age of twenty-seven and her mother was left penniless. The Warfields were not enormously rich but they were rich enough; they supported the widow and orphan. Wallis had a happy childhood; she adored her very pretty mother, who sent her to a fashionable day school in Baltimore. They lived for some years with her grandmother Warfield, who was kind but strict, and Wallis spent her holidays at the country-houses and farms of her uncles. The chief benefactor was her bachelor uncle, Solomon, a successful banker and President of the Continental Trust Company, whose office was known as Solomon’s Temple. He paid the school fees and other bills until Mrs Warfield married again; her new husband Mr J. F. Rasin, was fairly rich and like the Warfields and the Montagues, his family was prominent in politics. Wallis’ mother was well-known for her delicious food, and with Mr Rasin she gave delightful dinner parties in Baltimore.

Wallis was now sent to a boarding school, Oldfields, which had the motto: ‘Gentleness and Courtesy are Expected of the Girls at all Times.’ The motto was pasted on the door of every room so that it should never be forgotten, and even the basket-ball teams were called Gentleness and Courtesy. Many years later, writing in her memoirs of this emphasis on good manners at Oldfields, Wallis said she found it preferable to the modern way which led to the ‘uninhibited’ behaviour of young people.

Wallis was good at games and good at lessons. She made lifelong friendships at Oldfields and seems to have been perfectly happy there. The head-mistress, Miss Nan McCulloh, was old-fashioned and strict. As was the custom in those days there was a great deal of learning by heart; ‘Miss Nan’ would not allow any girl to go home for the Christmas holidays until she could recite a chapter of the Bible, word-perfect. While she was at this school Wallis’ step-father died in April 1913, and she and her mother became poor once again.

In 1914 she left Oldfields, signing her name and writing a message in the school book. Wallis wrote ‘ALL IS LOVE.’ The other girls’ contributions were painfully silly; ‘It’s the little things that count’, was one, another ‘Long live English history.’ Their cramped adolescent handwriting adds to the general impression of banality, whereas Wallis already had an adult, individual hand, her signature and her words springing from the page.

She made her début at a ball i

n Baltimore called the Bachelors’ Cotillion on 24 December, wearing a white satin dress with white chiffon tunic bordered with pearls. Her taste in clothes never failed her. But her Uncle Sol, who had given a ball for her cousin, refused to give a coming-out party for Wallis. In Europe the Great War had begun. He put a notice in the newspapers saying he could not give a ball for his niece Wallis Warfield ‘while men were being slaughtered and their families left destitute in the appalling catastrophe now devastating Europe.’ Eighteen months later catastrophe struck Wallis herself, though it did not seem so to her at the time.

Teackle Wallis Warfield, Wallis’ father who died a few months after she was born.

The summer cottage at Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania where Wallis was born on 19 June 1896.

Alice (Montague) Warfield with her daughter at about six months.

Wallis with her grandmother, a strict lady with an undying hatred of anyone north of the Mason-Dixon line

Wallis as a ten-year-old schoolgirl.

Oldfields, the boarding school in Baltimore, to which Wallis was sent in 1912.

Wallis as a debutante. The outbreak of the Great War in Europe had put paid to her hopes for a coming-out dance of her own.

Wallis aged nineteen. In 1915 she met the man who was to become her first husband, Win Spencer.

Although the usual festivities were somewhat curtailed by the distant war, Wallis seems to have had what all through her life she used to call ‘a good time.’ She and the other members of Baltimore’s jeunesse dorée had dances and parties in the evenings, and she spent the mornings in endless telephone conversations with her friends. Poor as they were, there was no thought of a job; just as in England at the same date girls like Wallis only had marriage to look forward to as a career. Not one of her class-mates at Oldfields had gone on to a university, let alone to a career.

The Duchess of Windsor

The Duchess of Windsor