- Home

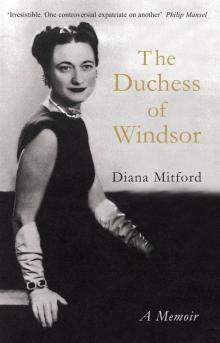

- Diana Mosley

The Duchess of Windsor Page 6

The Duchess of Windsor Read online

Page 6

It was Captain Ogilvy’s duty ‘to warn the Guard not to turn out in the small hours when HRH returned.’

Bruce Ogilvy’s mother, Mabell Lady Airlie, was always in waiting at Windsor for Ascot: ‘I used to go and see her every morning after breakfast and I told her all the goings-on of the night before.’ But unlike the Duchess of Devonshire, Lady Airlie told no tales.

Notes

3 Letter to the author.

* This suspicion was told to the author years later by the Duke of Windsor. The present Duchess of Devonshire, who was also there, asked him ‘Was she nasty when you met her face to face’ and the Duke laughed. ‘Nasty? Smarmy as be damned’, he said.

* During a visit to America the Prince was asked by Will Rogers what an ‘equerry’ was; he tried to explain, and Will Rogers said: ‘Well, Sir, I guess we have the same animal out in Oklahoma, only we call ‘em hired hands.

** Private secretaries.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Mrs Simpson meets the Prince

‘Come come’, said Tom’s father. ‘at your time of life

There’s no longer excuse for thus playing the rake;

It is time you should think, boy, of taking a wife,’

‘Why, so it is, father—whose wife shall I take?’

Tom Moore

AFTER TWO YEARS living in London, Wallis, now aged thirty-four, had made some English friends, and she also saw many visiting Americans as well as American diplomats en poste in London. Among the latter was Benjamin Thaw, First Secretary of the US Embassy, who was married to Consuelo Morgan. Mrs Thaw’s sisters were Gloria Vanderbilt and Thelma Lady Furness, the Prince of Wales’ friend of the moment. Wallis’ favourite cousin Corinne was also in London with her new husband, Lieutenant Commander Murray, Assistant Naval Attaché. Wallis had an excellent cook and she gave small dinner parties at Bryanston Court; also she was at home every evening at six when she made American cocktails for anyone who cared to drop in. As the old American song says: ‘Good times were round the corner.’

Mrs Simpson met the Prince of Wales through the Benjamin Thaws. They were to have been guests of Mrs Thaw’s sister, Lady Furness, in the country the following weekend when the Prince was expected, but Mrs Thaw had to leave for Paris because her mother-in-law had been taken ill there. They begged Wallis to take her place as chaperon. Although she was dying to meet the Prince, of whom she had heard constantly during her two years in London, Wallis at first refused. She would not know what to say to him, or how to curtsy, and it was a hunting weekend and she knew nothing about hunting. Mrs Thaw insisted; Benny Thaw would take the Simpsons down to Leicestershire and look after them in every way, she said. When Wallis told Mr Simpson about the invitation he was overjoyed; he said it was a great honour and they must certainly accept. Lady Furness telephoned to thank them for solving her problem, and on Friday afternoon they met Mr Thaw at St Pancras and took the train to Melton. On the journey Wallis made Mr Thaw show her how to curtsy; together they wobbled on the floor of the railway carriage.

A drive through dripping fog took them to the Furness hunting box, a modern, comfortable house. Wallis, who had a cold and felt a slight temperature coming on, wished she could go to bed, but when the Prince of Wales appeared the cold was quickly forgotten. Wearing loud checked tweeds he was accompanied by Brigadier General ‘G’ Trotter and by Prince George, who soon left because he was staying in the neighbourhood with other friends.

Wallis says she was surprised to discover that the Prince was so small. The royal family had inherited tiny stature from Queen Victoria; in those days ‘king size’ meant something miniature. She noticed his blue eyes, in which she detected a rather sad expression. She admired his natural, easy manners and the way he put everyone else at ease; she decided that he was one of the most attractive people she had ever met in her life. ‘Do you suppose he’ll every marry?’ she asked Benny Thaw, who replied that he had been in love with several women and added. ‘I rather doubt that he’ll ever marry now, having waited so long.’ As the Prince was only thirty-six Mr Thaw’s guess, which as we know was wide of the mark, may seem rather strange.

The visit to Lady Furness was in the autumn of 1930. That winter the Prince of Wales in his role of ‘Empire salesman’ left England for a lengthy tour of South America; he had learned Spanish for the occasion. Wallis saw the Prince twice more during 1931, both times at the Grosvenor Square house of Lady Furness. Once he gave her and Mr Simpson a lift home in his car and she invited him and General Trotter to come in for a drink, but they were on their way to Fort Belvedere. Wallis had been presented at Court, quite a feat for a divorced woman. She borrowed the dress and feathers from Mrs Thaw and Lady Furness and was photographed looking very elegant. It was the following January 1932, that a note came from the Prince inviting the Simpsons to stay at the Fort.

At this juncture it may be well to pause and look back at the story so far. As the whole world knows, the visit of Mrs Simpson and her husband to Fort Belvedere was to set in train a series of events which had grave consequences and caused a constitutional crisis of the first magnitude. Why this should have been is hard to understand; the reason lay deep in the character of the Prince himself and he is far and away the most important actor in the coming drama.

We have seen that his parents married because they were persuaded that it was their duty to do so. They became fond of one another but their feelings towards their children were mixed. The Queen, while admitting that the Prince made a quite exceptional impact on people wherever he went, and even admiring him for it, could not understand him. They were not in sympathy, she would have preferred a prince more aloof from his future subjects, less democratic. In the matter of friends, from her point of view he had gone from bad to worse. It must have seemed to her that he deliberately turned his back on suitable friends and on the English aristocracy. With her romantic view of royalty as a race apart she would have wished him to marry a royal princess, but since the war had made such a match difficult she would have been quite happy for it to be with a lady of noble birth. She had suffered in her youth from the fact of her father’s morganatic birth, and that she herself was not considered ebenbürtig by German princelings, but she had drawn first prize in the royal raffle by marrying the future King of England and she was conscious of playing her part perfectly. How doubly annoying, therefore, were ‘David’s fads’, one of which was his unaccountable liking for Americans. Instead of seriously looking about him for a wife he spent his spare time with Lady Furness, the American wife of a rich ship owner. The Queen was well aware that rich people of lowly birth had appealed to her father-in-law King Edward VII, but he was married to a royal princess and the succession was assured by the time he went yachting with his grocer, as his nephew the Emperor William II had disobligingly described his outings with Sir Thomas Lipton. She and King George V saw very few people except in the way of duty, but their household was composed of ladies and gentlemen of impeccable antecedents. She doubtless felt annoyed with the Prince in a number of small ways, particularly for dressing in what the King considered an outré fashion, with loud checks, turn-up trousers and enormous plus-fours. Her second son, the Duke of York, never teased his father in this way; furthermore the Duke had married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, and they had two little daughters, the older of whom was the apple of her grandfather’s eye. Queen Mary was anxious about the Prince of Wales, so charming and yet so obstinate. With her almost religious reverence for the Throne she could never understand why, even if her son might not feel obliged to do as his father wished about the width of his trousers, he did not immediately obey his King.

The King’s feelings about his heir were different, and verged on dislike. He disliked his way of talking, his cockney accent,* his way of dressing (clothes as the outward and visible sign of what was conventional and traditional were of the utmost importance to the King), his choice of friends, his pastimes, and above all his undoubted popularity. If the older generation of the aristocracy, taki

ng a cue from the King, sometimes secretly criticised the Prince of Wales, ordinary people, and particularly ex-servicemen, adored him. With a look or a word he managed to convey infinite sympathy and understanding in a way that was quite new in a royal personage. He combined the royal magic with the common touch, and no other member of the royal family came anywhere near him for magic.

Wallis in her flat at Bryanston Court in London.

Wallis wearing dress and feathers borrowed from Consuelo Thaw and Thelma, Lady Furness, when she was presented at Court.

The Prince in outlandish golfing attire—blue check shirt, grey plus-fours and check stockings—so disliked by the King (1933).

The Prince playing bagpipes.

The other principal personage in the coming drama was Wallis herself. She had hardly changed during the last years and was as thin as ever, which suited the fashions of the day. Her dark hair was plainly dressed, with a centre parting. Her clothes were simple but smart, already she bought them in Paris.

Since her careful and lady-like upbringing Wallis had not had an easy life, but her second marriage, though unromantic. had solved pressing problems. She was no longer homeless or penniless. She had an affectionate husband who appreciated her many qualities. He admired her talent for making friends, and the fact that her dinner parties were so successful and enjoyable and the food she provided so much praised. She collected interesting people, and with her gaiety and high spirits she made everything go with a swing. Now here she was arranging for them to stay with the Prince of Wales, an undreamed-of honour in Ernest Simpson’s eyes. They realized that the idea of the invitation had probably come from Lady Furness, but that did not detract from the glamour. Wallis was not nearly as excited about it as Mr Simpson, who, like Queen Mary, looked upon royalty as a race apart, and who could hardly believe his luck.

* It was a faint, but unmistakable cockney accent. For example, he prononounced ‘lady’ almost ‘lidy.’ In later life he acquired certain American intonations.

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Prince in Love

Krone des Lebens,

Glück ohne Ruh’

Liebe, bist due!

Goethe

FORT BELVEDERE IS a grace and favour house belonging to theCrown situated six miles from Windsor Castle. It is a castellated eighteenth-century folly, added to by Wyatville. The Prince had asked his father if he might have it. ‘What could you possibly want that old place for?’ said the King. ‘Those damn weekends I suppose.’ However he let the Prince have it, and the Fort became his home, where he did as he liked when he was off duty, and had his friends to stay. He made it comfortable inside and put Canalettos in the drawing room and horse pictures by Stubbs in the dining room, but his joy was the garden, over-grown and neglected, which he was gradually transforming into his very own paradise.

This first weekend with the Simpsons was a great success, though the unfortunate Ernest, who detested physical exertion, was roped in to help the Prince cut down and clear away untidy old laurels which disfigured the garden. When he hesitated, General ‘G’ Trotter told him: ‘It’s not a command but I’ve never known anyone refuse.’ Simpson joined the laurel-slashers. In the evenings the Prince did his embroidery, he told Wallis he had learnt how to do gros point from Queen Mary. Then they danced to the gramophone. Wallis was impressed by the Prince’s simple tastes and by the relaxed atmosphere at the Fort. She found the Prince of Wales extraordinarily attractive, but there was no question of a coup de foudre on either side. It was a friendship which gradually developed. She and her husband were invited to the Fort several times in 1933, and when it was realised that they had become friends with the Prince they began to be asked to dinners and parties by dozens of English people who would never have noticed them in the ordinary way. When Wallis spent two months in America the news had reached Maryland, and already there was an atmosphere of local-girl-makes-good in Baltimore.

Fort Belvedere, an eighteenth-century folly in Windsor Great Park, described by the Prince as a ‘pseudo-Gothic hodgepodge.’ The gardens at Fort Belvedere were wild and overgrown and one of the Prince’s favourite occupations was to clear the laurels.

A tea party at the Fort, 1934. From left to right, Euan Wallace, Wallis, Evelyn Fitzgerald, Barbie Wallace, the Prince, Hugh Lloyd Thomas, and Mrs Fitzgerald.

Thelma, Lady Furness.

Back in London early in 1934 Lady Furness told her that she was going to America with her twin sister Gloria Vanderbilt for six weeks. ‘Oh Thelma, the little man is going to be so lonely,’ said Wallis. ‘You look after him for me,’ was the reply. While Lady Furness crossed the Atlantic in a glare of publicity with Aly Khan showering red roses and other attentions on her, Wallis looked after the Prince. She gave little dinner parties for him at Bryanston Court, and she encouraged him to talk about his work. ‘Wallis,’ he told her, ‘You are the only woman who has ever been interested in my job.’ The Bryanston Court flat became his home from home. Whenever he had time he dropped in for a chat and a drink and stayed on and on, often until Mr Simpson got back from his office and they had to suggest dinner. Rather quickly Wallis became indispensable to him and he lived for the moment when they would be together.

By the time Lady Furness returned from America Wallis was firmly established as the Prince’s greatest friend. She was not only a sympathetic and affectionate companion when they were alone, she could also be the liveliest and most amusing person at a party, the one who made everything more fun. Moreover she had what was for the Prince a unique attribute, her complete naturalness. It was something she never lost. She was probably the only woman he ever met who did not feel obliged to behave slightly differently because he was there to the way she would have with anyone else. The Prince was one of the most sensitive beings ever born and he detected the falseness in people’s approach to him immediately. He liked Americans because they were less awed by his position than English people were apt to be, but even with them there was as a rule the desire to impress, or to be impressed, or even to make naturalness into an act which he could see through.

Wallis was quite different. She was always very polite, curtsying, calling him ‘Sir’, but she always spoke her mind. It must have made him feel that at long last here was someone who treated him as he would have wished. To the end of his life he remained ‘very royal’ (in the words of Lord Tennyson, whose parents had been friends of the Prince and who saw him often in France during the fifties and sixties). He never allowed people to be casual or off-hand with him, let alone impertinent or insolent. He wanted exactly what Wallis gave him, natural and unaffected good manners.

At the same time he was very much attracted by her, She was his type of woman, small and thin, beautifully dressed. He admired her efficiency, the trouble she took about details. And he loved her jokes and her wisecracks and her rapid response to the jokes of others, her irrepressible gaiety. She could talk, and she could listen. Like him, she learnt from people what can hardly be learnt from books. He fell deeply, obsessively and permanently in love with her; it happened gradually and once it had happened he remained in love with her until the day he died. He was constant as the northern star.

Bruce Ogilvy writes: ‘After Thelma Furness had realised that all was over between her and the Prince of Wales, “G” Trotter, who was a friend of hers, took her out to dinner and of course talked about the whole affair. The Prince got to hear of this and had “G” Trotter up and just sacked him on the spot because of what he had said to Thelma Furness. I think it really broke G’s heart because he had been very fond of the Prince of Wales and really a great friend.’ This was the first of a series of rather heartless actions on the part of the Prince who could not tolerate even the faintest disloyalty, or what he chose to look upon as disloyalty, towards Wallis. His love for her filled him to the exclusion of all else, even of old friendships. Although the great public knew nothing of the Prince of Wales’ friendship with Mrs Simpson a fairly wide circle in London knew of it, and those who di

d thought at first it was just Lady Furness over again and Wallis the Prince’s latest

American friend. Society being what it is, Wallis began to have not just a good time but the time of her life. She was courted and flattered. Mr Simpson, however, knew very well that if the Simpsons had become such a centre of attraction for all the snobs in London it was certainly not because of him. He absented himself more and more, and in fact behaved with dignity. Mrs Simpson saw only the Prince. If she had seen others, everyone would have known, even if there was nothing in the newspapers.

Rumours of the romance reached Buckingham Palace, but probably beyond regretting one more obstacle to a suitable marriage the Queen at first paid no attention. As we shall see, the King’s attitude was completely different from hers.

In the summer of 1934 the Prince took a villa at Biarritz and invited Wallis, with her Aunt Bessie as chaperon. They had not been there very long when Lord Moyne appeared in his yacht. His companion was Posy, wife of his cousin Kenelm Guinness. Lord Moyne invited the Prince and Wallis to cruise with them to the Mediterranean. He was an intrepid sailor and took them through some very rough weather, but they eventually reached calm seas and anchored off Formentor, a beautiful beach on the enchanted island of Majorca, in those days a lonely paradise.

Wallis wrote in her memoirs that the cruise on Rosaura was a turning point. The Prince was now undoubtedly in love with her. ‘Searching my mind I could find no good reason why this most glamorous of men should be seriously attracted to me,’ she says modestly. ‘I certainly was no beauty, and he had the pick of the beautiful women of the world. I was certainly no longer very young. In fact in my own country I would have been considered securely on the shelf [Wallis was now thirty-eight].’ She goes on to give the reason for this interest in her: directness, independence of spirit, sense of humour. ‘Perhaps it was this naturalness of attitude that had first astonished, then amazed and finally amused him.’ Amused? Maybe, but captivated certainly. ‘Then too he was lonely and perhaps I had been one of the first to penetrate the heart of his inner loneliness, his sense of separateness.’ All true, no doubt, and Wallis had other qualities which she does not mention, one of which was courage. What she lacked was an understanding of England and English life and English ways, but however expertly she had surveyed the situation in which she found herself the end result would have been the same.

The Duchess of Windsor

The Duchess of Windsor